Art Of Storytelling

The essence of a good story is not so much a lofty moral or an expansive story arc – though there’s nothing wrong with those, if well executed – but rather the handling of the individual scenes along the way. It’s the small details that draw you in and get you hooked. At his best, Billy Connolly was a prime exponent of the art.

James Joyce added another layer to this insight with his oft-quoted observation: “In the particular is contained the universal”.[1] You can touch on the essentials of the world-wide human condition without your story ever leaving a single village located at the back of beyond. The early films of Satyajit Ray bear out the truth of that.

With those thoughts in mind, I’d like to offer my take on Karine Polwart’s A Pocket Of Wind Resistance, a CD released in November 2017 in collaboration with Pippa Murphy, composer and sound designer.

In the sleeve notes to the CD, Polwart modestly counsels that “This is an album unlike any other I’ve made. It won’t be to everyone’s taste.”. Certainly, it’s an ambitious piece of work.

Not simply a collection of themed songs but rather an extended essay, mixing spoken word narration, sound effects and music. What sets it apart from the unlamented concept album of the 1970s is both its intelligence and its self-control; there’s no descent into pomposity and no filler material to pad out a thin plot. Despite the ambition, Wind Resistance keeps its feet firmly on the ground – though not literally – and it’s all the better for that.

There are two intertwined stories here: that of the migration of the pink-footed goose from Iceland and Greenland to its winter getaway of the countryside bordering the Firth of Forth (near to Polwart’s own home) and that of a young couple of the same area in the years just after World War I. Neither of those is earth-shattering of itself; but, it’s the way the details are handled that is so special. The storytelling is both adept and full of charm.

Dominion Over All Things

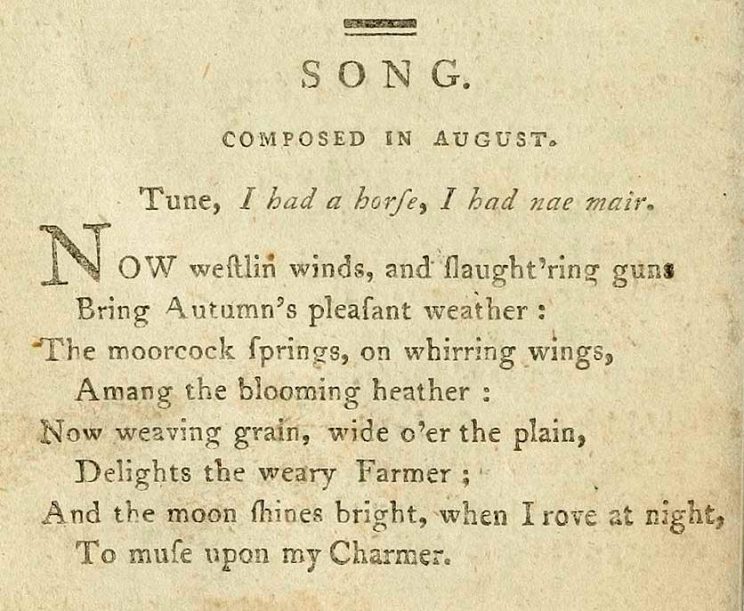

In terms of the music – or, at least, the songs – the centrepiece of the album is Tyrannic Man’s Dominion, which is based on Now Westlin’ Winds (or Song Composed In August) by Robert Burns. My immediate thought on hearing this was that it owed a lot to the version of the song as performed by Dick Gaughan. The sleevenote for the track does indeed acknowledge this.

Polwart describes Gaughan’s version as “never-to-be-bettered”. As a Gaughan devotee, my instinct would always be to take that as the default position regardless. In this case, however, I’m going to disagree with Polwart. The arrangement is close to the one Dick used, but the delivery is very different. Whereas Gaughan snarls with righteous anger, Polwart’s is a gentler take, which is in keeping with the context it’s placed in here. It may be gentle, but it’s certainly no less firm of view. The guitar playing is a joy and Polwart’s singing on this is surely among the best of her recorded output.

The recording is superb and it ranks up there with Gaughan, perhaps even surpassing him. It’s possible that it won’t work so well for some if listened to out of its storytelling context, because the CD track includes some spoken narration and also a snatch of another song; but I’d hope that wouldn’t prove an issue for most. For my own private listening I made an edit of the track that consists solely of the principal song itself (which takes 2½ minutes off the length) and I’m playing that on repeat as I write.

(If you’re reading this, Karine, how about an official release of the song on its own?)

Love Is All There Is

Once we’re past the initial scene-setting, the young couple’s love is marked by a rendition of Lark In The Clear Air. Originally a Victorian prose poem, this was matched with a traditional Irish air and has been delivered in countless plodding performances since. (The choral ones are the worst.) Polwart’s version rises above that mediocre precedent, though, giving the tune a lovely lilting quality which stops it dragging, but all the while retaining the period feel of the lyrics.

The introduction to Lark is by way of a brief scat vocal section. It’s bubbly and infectious. Just like being middle-aged and having to endure the company of youngsters flushed with passion, oblivious to all but each other: we shake our heads at the naivety of it, but privately are enviously nostalgic for our own lost youth. It’s a charming moment or two, but it would probably also start to grate if it went on for long, which it doesn’t do. The addition of this passage to the song is one of the small details that really make a difference with this whole work.

As soon as Will and Roberta Sime are made known to us, it’s not difficult to guess how their story will play out. We’re given enough clues along the way and it wasn’t an unusual fate at the time in any case. The events are firmly located in a rural farming setting in Central Scotland, complete with specific local references. It’s also a true story, in the sense of being taken from real life.

It may be a common one and it may be distinctly “placed”, but if this tale is to be labelled “commonplace” then that should be taken as a compliment in the Joycean fashion. Polwart’s storytelling prowess elevates this account into one of universal interest and relevance.

Given the specificity of the geographical setting for the work as a whole – Midlothian in Central Scotland – it comes as a bit of a surprise when the story takes an abrupt detour, to include the death in childbirth of Jane Seymour, consort to Henry VIII of England.

It jarred at first for me because of that dislocation in space and time. Then things fell into place: it does fit perfectly into the flow of the story arc after all. The setting may be very different, but those particulars shouldn’t matter if the sentiments are universal, as they are here. In any event, it’s another great rendition of a traditional song, well played and sung.

The Flying V

The migrating geese form the other half of the story here. Not in terms of a superficial description of the annual relocation, but instead in what Polwart suggests we can learn from the way the geese collaborate to make the arduous journey possible. It’s in creating a system of “pockets of wind resistance” that the birds in the lead assist those behind and below, with the chore being successively passed on through the ranks in a huge co-operative effort:

stepping up, falling back

labouring and resting

stepping up, falling back

labouring and resting [2]

As serious as the piece is overall, it’s not without its flashes of wit, albeit it’s a dark humour laced with pathos. There’s this reporting for example of the mishap befalling a pair of swallows trying to raise their offspring at the farmstead of Will and Roberta:

“From the Orange River delta in South Africa, across the Congolese rainforest and the desert skies of the Sahara …

the Atlas Mountains of Morocco … the eastern edge of Spain … the Pyrenees, and the full length of France and England,

only to see their nest, their brood, fall from the worn stippling of a Midlothian farmhouse wall.” [2]

More Like Geese

There are the explicit stories of the geese and the Simes, but there’s also another strong strand to this work, which is a political one. As Polwart said in a newspaper interview published in December 2016:

“Politically to me that’s the big issue of our times. The incremental erosion of the idea of collectivism and the idea of universal care. Our NHS is under threat. …. So Wind Resistance is my own little form of rally, saying ‘we need each other’.

Your lone goose trying to fly from Iceland is toast. It’s not going to make it. So could we just think of ourselves a little more like geese?”. [3]

The CD is framed as a “companion piece” to a stage show, which is titled simply Wind Resistance. This latter is a longer work, with much more by way of expository material, covering history and folklore, aerodynamics in the natural world and personal memoir. Making appearances along the way are archaeology, medieval medicine and even a certain Scottish football manager.

Somehow, I managed to miss the Wind Resistance show when it was staged as part of the 2016 Edinburgh Festival and also the Celtic Connections slot in Glasgow early in 2017.

The good news is that Perth is seeing a further six performances, from 17th to 22nd April of this year, and I’ll be making the trip to the Fair City to catch one of these, even if I have to jump on a passing goose to get there.

Long Live The NHS

The book of the show – not your normal text of a play, but more of a prose poem in its own right – does help to explain one part of the CD where the narrative in the 3rd person switches into a 1st person description of direct involvement. I had assumed it to be simply a literary device. It may well still be viewed as that within the context of the CD, but its source is a larger section of the stage show in which Polwart shares with us her own experience of giving birth for the first time.

Which brings me to my own story about the politics of childbirth and support for the NHS. When our third child was born, my wife and I wanted to include in the birth announcement a note of thanks to the NHS.

The advertising dept for the newspaper concerned phoned to tell us that they would not be accepting the comment on the NHS, however, and what was actually printed did omit that part. I complained, drawing a comparison with the willingness to include in the paper adverts for adult chat lines and the like.

To be fair, the editor at the time wrote back promptly, acknowledging that it seemed a “curious decision” to him as well. (Click on the image below to see the detail.)

Despite the conciliatory tone struck by the editor, it took a bit more correspondence before they relented and printed the announcement in full.[4]

What I had explained in my complaint was that:

“Thanking the National Health Service was for us more than a simple gesture of political partisanship. We benefited from an arrangement governing the care of mother and baby during labour and the post-natal period which is available from the NHS only, and not from any other agency.”.

That particular service was at that point under threat of withdrawal. The rationale was that it wasn’t being used enough. (Not surprising really as it wasn’t well publicised.) We wanted to lend support to its continuance by expressing our appreciation publicly.

It needs repeating endlessly: the NHS is our greatest collective achievement. Private medicine thrives because it is allowed to cherry-pick, leaving the most burdensome, risky and expensive tasks to the NHS and it is for that reason that you cannot realistically replace the NHS with a fully private service (even one on an insured basis). Simple-minded comparisons between the two are flawed, therefore.

The notes on the CD cover for A Pocket Of Wind Resistance sign off with the exhortation “LONG LIVE THE NHS”. Amen to that.

Feather In Cap

Karine Polwart may have feared that this album wouldn’t be to everyone’s taste, but she shouldn’t worry if that has turned out to be the case, because you simply can’t please all the people all of the time. (Just ask James Joyce about that…)

What matters is that, for those who care to listen, this really is a wonderful achievement, a joy from beginning to end.

Footnotes

1. “For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.” – James Joyce to Arthur Power, 1922 in Paris.

2. All lyrics and other text quoted are the copyright of Karine Polwart.

3. The full interview is available via this link.

4. What was particularly strange was that we had used the offending wording previously without any objection being raised.